This article is an on-site version of Free Lunch newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Thursday and Sunday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Happy Sunday. Over 100mn people — mostly in Asia — are expected to join the middle class every year. Having just returned from vibrant Vietnam, I can see why.

This week, however, I wanted to focus on the state of the middle class in the west.

Over recent decades, the very top and bottom ends of the income (and wealth) distribution have dominated political discourse — from the global financial crisis to the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the spotlight on inequality has obscured what’s happening to the majority in the middle. Here’s what I found — and why it matters.

Reports of middle-class anxiety are becoming more common across the developed world.

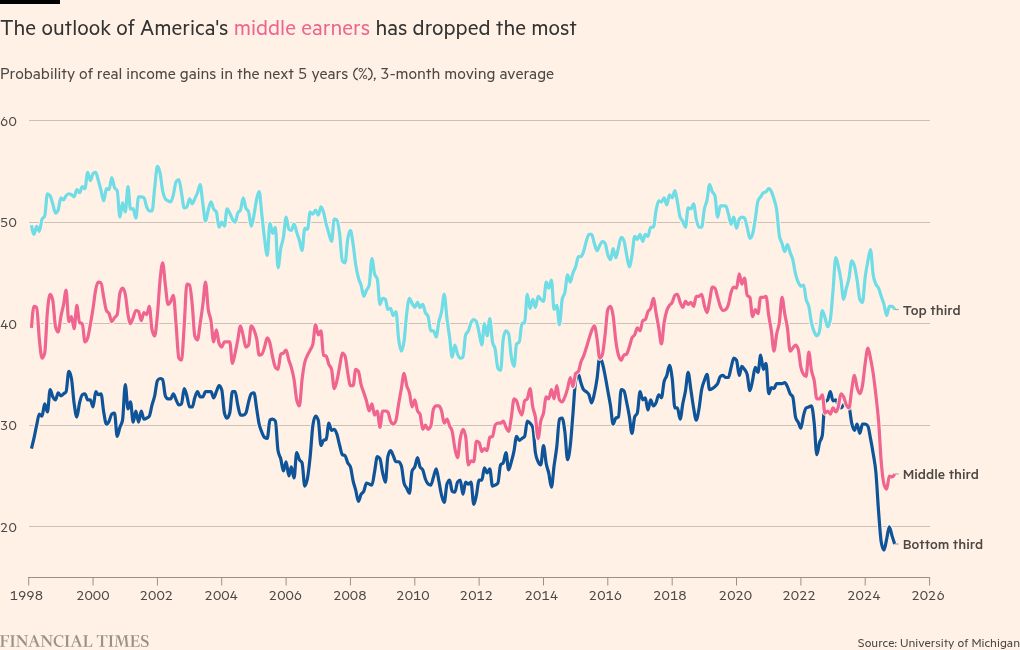

Since 1998 in the US, earners across the income distribution have become less optimistic about their future real income gains. But the drop has been most stark for those in the middle.

In Europe, the middle class’s financial struggles have been frequently highlighted in surveys. A recent report by abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, a research body, finds a rising sense of insecurity and financial strain among Britain’s middle earners.

What explains the middle class’s pessimism? Weak income growth is an obvious first culprit.

The share of middle-class people in developed economies shrank between the mid-1980s and 2010s, according to the OECD. (It defines the middle class as households earning between three-quarters and double the median income.)

In the US today, just over 50 per cent of the population is considered middle class according to the Pew Research Center (based on a similar definition). That’s down from closer to 60 per cent in 1971.

Between 2007 and 2022, almost two-thirds of EU countries experienced a drop in middle earners, based on research by Eurofound. This was predominantly driven by people falling into the lower class, including in some of the most developed economies.

Real disposable incomes have risen most among the top earners in advanced economies. But lower and middle earners have generally experienced tamer earnings growth over the first two decades of this century.

Poor productivity has restrained employees’ wages. Economic shocks — including the global financial crisis, austerity and the pandemic — have jolted households in the middle too.

But the middle is an amorphous group, and defining it on income alone can be limiting. For instance, some “middle class” salaries have risen faster than others. Asset wealth matters too. And even those in traditionally well-paid jobs have not been able to beat inflation.

Indeed, surveys suggest there are a broad swath of unhappy people in the middle between the poor and the uber-rich — not just around the median — stretching from young graduates to established professionals.

In Britain, about one in four earning above £100,000 a year — more than double the median, full-time salary — say they are living pay cheque to pay cheque. In the US, more than half of six-figure earners report the same. They are sometimes referred to as Henrys (high earners, not rich yet).

Rather than focusing on income, assessing middle class aspiration itself could be more informative. It is generally associated with university education, professional occupations (such as accountants, lawyers and doctors), stable employment, home ownership and raising children.

Degree-holding professionals — and those who want to become such — are often embarrassed to admit their financial anxieties, particularly when there are plenty of more vulnerable households.

Part of their frustration could merely be comparative.

To illustrate, since 1975, the real household income ratio between the top 5 per cent of earners in the US and the 70th percentile has risen by about 30 per cent. At the same time, the ratio of the 70th percentile to the bottom decile has risen just over 20 per cent.

Breakaway among the very rich isn’t too surprising. High salaries and bonuses can be invested in assets — such as stocks and property — which in turn can generate new revenue streams. Supernormal profits in the tech industry have also spawned a new generation of millionaires and billionaires.

In some cases at the other end, state support for those on lower incomes has driven wage compression between them and those starting out in professional careers.

“Entry-level grad salaries are lower now than pre-financial crisis in real terms,” said Nye Cominetti, principal economist at the Resolution Foundation think-tank, referring to the UK. “But a full-time minimum wage worker is doing much better than pre-financial crisis.”

Over recent years in Britain, the full-time salary of a fresh graduate at the bottom of the graduate pay scale has converged with that of workers on the state statutory wage. That’s before considering the costs of going to university.

For those in the middle, the feeling of not closing in on those above you while not moving much further from those below can evoke a sense of stasis — and imply low returns to ambition.

But costs are probably the biggest source of pessimism among the middle. The chart below is inspired by Mark Perry, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, who describes it as “the chart of the century”.

It shows that the price of essentials in the US — such as housing, healthcare, child support and tuition — has become significantly more expensive since the start of the 2000s. It has vastly outpaced growth in average hourly earnings too. It’s a similar story elsewhere in the developed world.

“Goods and services provided by the private sector get more and more affordable over time, especially for goods with foreign competition, like cars and toys,” said Perry. “But those provided or funded by the government or provided in highly regulated sectors get less affordable over time.”

The rising cost of essential services means middle class aspiration gets relatively more expensive, particularly as salaries can’t keep up. It also limits the room for savings and pensions. Borrowing has helped bridge the gap (but higher interest rates make that expensive too).

The struggles of the majority in the middle should not detract from the well-documented challenges of more vulnerable, low-income households. But when building a stable life as an ambitious professional with a family feels increasingly fraught, it’s clear that something needs fixing in the west.

For starters, productivity growth is vital to boost wages. More houses need to be built, and public services need to become more efficient. That will take time. In the interim, many in the middle fret that their jobs will be replaced by artificial intelligence or professionals in developing countries willing to work for less. Upskilling opportunities throughout life need improving.

The vast middle represents a significant chunk of the tax and voter base. But more and more professionals in America and Europe are considering building their life abroad. The struggles of the west’s best and brightest ought to alarm politicians. Losing them to other countries would only make things worse.

Thoughts? Rebuttals? Message me at freelunch@ft.com or on X @tejparikh90.

Food for thought

This week’s stock market frenzy over China’s DeepSeek large language model vindicated Free Lunch on Sunday’s analysis a few weeks back on how Beijing’s agility will allow it to swerve US protectionism. This article in Nature outlines just how China managed to shock the world.