On the witness stand in March 2000, Dr. Janet Squires was unequivocal: The injuries suffered by the 13-month-old girl were “absolutely classic” signs of shaken baby syndrome. Commonly referred to by its acronym, SBS is a diagnosis based on the belief that a certain combination of injuries found in a baby or toddler could only be caused by violent shaking.

“When a baby is shaken their head flops back and forth like this,” she testified, demonstrating the violent force needed to cause injury. “And the rotational forces through the brain literally sort of shear the tissues of the brain.”

Coming from the then-director of pediatrics at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, Squires’s testimony would be crucial to the conviction of Andrew Wayne Roark, who was sentenced to 35 years in prison for violently shaking his girlfriend’s daughter, causing permanent brain damage.

Roark insisted he was innocent. Three years earlier, in July 1997, Roark was babysitting the child, referred to in court documents as B.D., while her mother was at work. He took B.D. to the doctor for a regular check-up, then fed her ravioli for lunch before giving her a bath. According to Roark, the infant slipped in the tub, hitting the back of her head, but she seemed fine and Roark put her down for a nap. When he went to check on her, however, he found her face down next to the bed. She was limp, pale, and barely breathing. Roark called 911. At Children’s Medical Center, Squires determined that B.D. had been violently shaken. Roark was arrested that night and charged with injuring her.

A few years later, Squires would play a key role in securing a guilty verdict against another man, Robert Roberson, whom she said had violently shaken his 2-year-old daughter to death. “You really have to shake them really hard back and forth and then you typically slam them against something,” she testified at Roberson’s trial. “It’s an out of control, angry, violent adult.” Roberson, who maintained his innocence, was sentenced to death. (Squires did not respond to The Intercept’s request for comment.)

In the years after both men were sent to prison, the symptoms once believed to be indicative of SBS were called into question. For years, doctors like Squires had claimed that a triad of symptoms — subdural hematoma, brain swelling, and retinal hemorrhage — could only be explained by violent shaking. But subsequent research demonstrated that it is physically impossible for a human to cause such injuries by shaking alone and that each of the symptoms could be the result of myriad medical causes. To date, 34 people convicted based on SBS have been exoneratedaccording to the National Registry of Exonerations.

In 2013, Texas enacted a first-of-its-kind law, allowing people prosecuted on the basis of junk science to challenge their convictions. Roark successfully argued to his trial court that SBS had been discredited and that he was entitled to a new trial. Last week, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agreed that key medical experts in Roark’s case would not testify the same way if the trial were to take place today: “We find that if the newly evolved scientific evidence were presented … it is more likely than not, he would not have been convicted.”

Like Roark, Roberson challenged his conviction under the state’s junk science statute and presented evidence to his trial court that the experts against him had relied on supposed symptoms of SBS that have since been discredited.

But unlike Roark, the judge in Roberson’s case disagreed that a change in the science had undermined his conviction. The Court of Criminal Appeals signed off on the judge’s conclusions, providing no explanation for its decision and clearing the way for Roberson’s execution. Texas plans to kill him on Thursday.

The Court of Criminal Appeals’ decisions in the two cases leaves an irreconcilable disparity: In Roark’s case, the court concluded that expert testimony about SBS was unsupported by science, while simultaneously deciding, in Roberson’s case, that it’s perfectly fine to send a man to the death chamber based on such testimony.

“The same prosecution expert testified in both trials making many identical pronouncements about how shaking had to be the principal explanation for the child’s brain condition,” said Roberson’s attorney, Gretchen Sims Sween, who has been fighting tirelessly to save her client’s life. “The flaws in the expert testimony are nearly identical.”

Nevertheless, the Court of Criminal Appeals refused to reconsider its ruling against Roberson in light of Roark’s case. Unless the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and Gov. Greg Abbott intervene to offer him clemency, Roberson will this week become the first person in the U.S. executed based on the debunked diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome.

Photo: Courtesy of Gretchen Sween

Angel of the Innocent

Nikki was unconscious and her lips were blue when her father Robert Roberson found her in bed the morning of January 31, 2002.

The 2-year-old had been ill the previous week: coughing, vomiting, and running a high fever. Roberson had taken her to the doctor twice and both times was sent home with drugs that, today, would not be prescribed for children her age. The night before Roberson found his daughter unconscious, Nikki had fallen out of bed; he’d comforted her and everything seemed fine. Now, she was unresponsive. Roberson rushed Nikki to the local hospital in Palestine, Texas.

Although medical personnel were able to restart Nikki’s heart, she was already brain dead. They found one lump on the back of her head and took scans of her head, but found no signs of abuse. Nonetheless, they decided that Roberson was acting odd; he wasn’t as emotional as they believed a father should be given his daughter’s grave condition. They immediately called the police. Upon his arrival, Palestine Police Department Detective Brian Wharton also noted that Roberson was stoic and detached.

Before an autopsy had even been performed, Roberson was arrested and charged with killing Nikki.

Nikki was transferred to Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, where she was examined by Squires. A renowned pediatrician known for pioneering treatment of children with AIDS, she had more recently turned her attention to cases of child abuse. A few years earlier, in a Christmas Eve feature, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram had spotlighted Squires as one of the community’s “angels,” naming her “Angel of the Innocent.” Squires quickly concluded that Nikki had been a victim of shaken baby syndrome. “There was some flinging or shaking component, which resulted in subdural hemorrhaging and diffuse brain injury,” Squires told police, along with an “impact” area on the back of Nikki’s head, which she declared was not related to the child’s fall from bed. Before an autopsy had even been performed, Roberson was arrested and charged with killing Nikki.

The following year, he was convicted and sentenced to death based largely on Squires’s claims, which were even accepted by Roberson’s defense lawyer, who said that Nikki had been killed due to violent shaking, which occurs when an adult loses control of their emotions. “It’s a bad thing,” the lawyer told the jury, “but it’s not something that rises to the level of capital murder.”

Roberson insisted he was innocent. In 2016, he challenged his conviction under Texas’s junk science law. He was a week away from execution when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals sent his case back to a trial court. During a nine-day evidentiary hearing, Roberson’s lawyers argued that SBS had been debunked and presented new evidence that undermined the state’s insistence that a crime had even occurred. A neuropsychologist who evaluated Roberson diagnosed him with autism and testified that the perception of his behavior as inappropriate by police officers and others was a misunderstanding of his neurodivergence.

Perhaps most important, Roberson’s lawyers presented crucial evidence that offered alternate explanations for Nikki’s death. Medical experts testified that Nikki was seriously ill with undiagnosed pneumonia and that the drugs she’d been previously prescribed had likely made her condition worse. And, in contrast to Squires’s insistence that Nikki’s head injury could only have been caused by a violent act, medical experts at the hearing said the evidence was consistent with Nikki having fallen off the bed, just as Roberson had described.

Notably, the prosecutor didn’t call Squires to testify at the hearing, claiming the doctor could not be located.

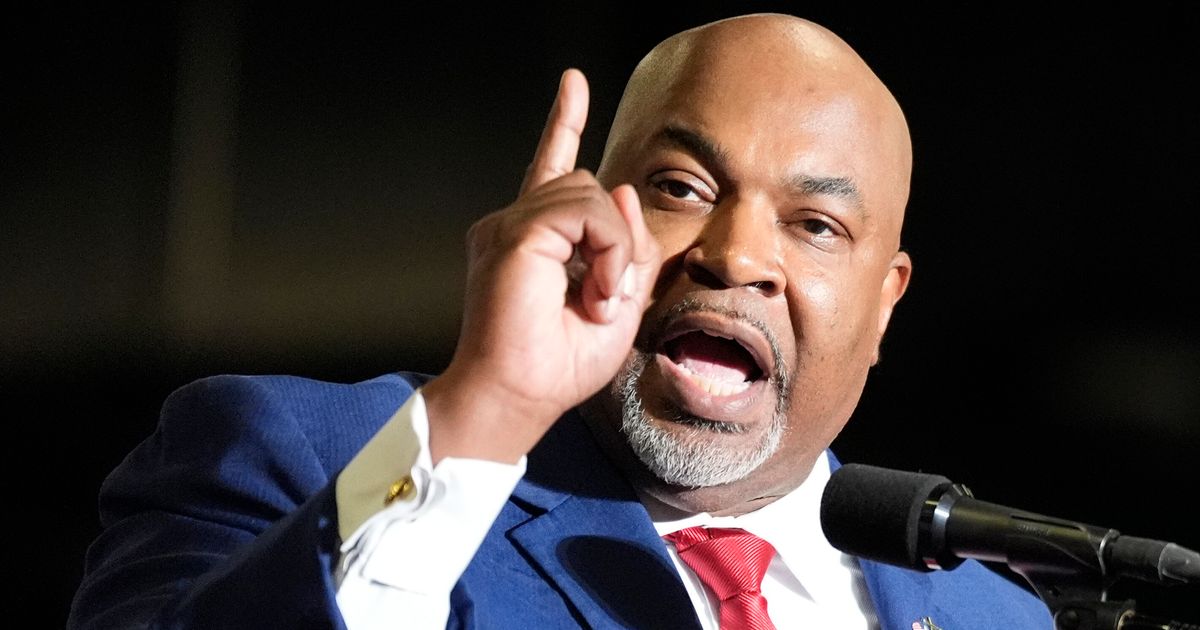

Photo: Criminal Justice Reform Caucus via AP

We Were Wrong

Given all the similarities between the Roark and Roberson cases, it is hard to square their sharply different outcomes before the courts. Yet there are notable differences: The Dallas County District Attorney’s Office agreed that Roark’s case deserved a second look, while prosecutors in more rural Anderson County have stuck by Roberson’s conviction. And in Roark’s case, Squires conceded in an affidavit that a relatively minor portion of her testimony was inaccurate, but stood behind the broader SBS diagnosis. When Roberson’s attorneys reached out to Squires, she never responded.

Nevertheless, it remains true that the Court of Criminal Appeals has signed off on Roberson’s execution even though it featured the same flawed forensic testimony the court said required a new trial for Roark. This has happened before.

Cameron Todd Willingham and Ernest Willis were convicted of strikingly similar arson crimes based on the same flawed fire science. In 2004, Texas executed Willingham; Willis was exonerated later that year.

The Willingham execution sparked outrage and pushed Texas to confront the problem of wrongful convictions and flawed forensics, helping to lay the groundwork for the passage in 2013 of the state’s junk science law. The law was meant to prevent miscarriages of justice, but in the most high-stakes cases, like Roberson’s, it has not worked as intended. According to a recent report from the Texas Defender Service, no one on death row has ever successfully challenged their conviction under the junk science law.

Two decades after Texas executed an innocent man based on junk science, it is on the verge of doing so again. Though the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and Gov. Greg Abbott can act to spare Roberson’s life, there’s little reason to think they will.

Under Texas law, the governor needs a recommendation from the board in order to grant clemency; without the board’s recommendation, the governor is only empowered to issue a one-time, 30-day reprieve. State law does not require that the board grant Roberson a hearing or even that it discuss his application for clemency. Historically, board members have not met to discuss clemency for people on death row and instead members have merely faxed in their individual decisions. Under Abbott, just a single person on death row has had their sentence commuted.

In asking the board and Abbott for mercy, Roberson has assembled an impressive clemency petition that includes letters of support from medical professionals, families who have been erroneously accused of child abuse, and a bipartisan group of Texas lawmakers, some of whom have traveled to death row to pray with Roberson.

Also asking for the state to spare Roberson is Wharton, the former Palestine detective who investigated Nikki’s death. Now a Methodist preacher, he has been vocal about his regret over the role he played in sending Roberson to death row. In a letter to the board, he wrote that he was never comfortable with Roberson’s conviction and hoped for years that the courts would intervene.

“We, the State of Texas, are now working only to protect our capital system and a conviction,” Wharton wrote. “We have failed to hear Robert’s righteous plea of innocence. We rushed to judgment. We were wrong, the jury was misinformed, and Robert is not guilty of any crime.”