On a chillyearly morning in January 2019, a group of animal rights activists descended upon a poultry farm in central Texas. Donning plastic gloves, medical masks, hazmat suits, and T-shirts emblazoned with “Meat the Victims,” they slipped through the unlocked door of a massive, windowless barn.

Inside, they found 27,000 chicks densely packed across the floor, like “just a sea of yellow,” recalled Sarah Weldon, one of the activists. “There were a lot of chicks that were already deceased, in various stages of decomposition,” she said. “Some were so deformed you couldn’t even tell they used to be baby chicks, just fluffs of feathers.”

Activists with Meat the Victims, a decentralized, global movement to abolish animal exploitation, later uploaded gruesome photos of injured and dead chicks to social media platforms. This is how, Weldon suspects, the police identified her and issued a warrant for her arrest, along with 14 other activists. She was charged with criminal trespassing, a Class B misdemeanor, and quickly turned herself into jail.

The local police weren’t the only ones paying attention. An FBI agent in Texas had been secretly monitoring the demonstration. His focus? Weapons of mass destruction.

The FBI has been collaborating with the meat industry to gather information on animal rights activism, including Meat the Victims, under its directive to counter weapons of mass destruction, or WMD, according to agency records recently obtained by the nonprofit Animal Partisan through Freedom of Information Act litigation. The records also show that the bureau has explored charging activists who break into factory farms under federal criminal statutes that carry a possible sentence of up to life in prison — including for the “attempted use” of WMD — while urging meat producers to report encounters with activists to its WMD program.

“The very framing of civil disobedience against factory farms as terrorism is a form of government repression.”

Animal rights lawyers and advocates view this new frontier for WMD allegations as a pretense, a fictive way to legitimize the criminal prosecution of animal rights activists.

The FBI declined to comment on these plans or clarify whether it is still actively considering charging activists under statutes for WMD.

“This kind of escalation in charging or threats of charges is textbook escalation by government actors against successful efforts by social movements that they disagree with or find subversive,” said Justin Marceau, a law professor who runs a legal clinic for animal activists at the University of Denver. “The very framing of civil disobedience against factory farms as terrorism is a form of government repression.”

The bureau has floated the idea of charging animal rights activists under a statute prohibiting biological weapons, a subtype of WMD, the records show. This may include toxins, viruses, and microorganisms used to deliberately spur death and disease.

Marceau described this focus on agroterrorism as an effort to pin blame on activists for the rampant disease outbreaks on factory farms.

“It’s a transparent form of scapegoating and blame shifting” that avoids “talking about the disease risks that come from having animals intensively confined in these high stress conditions,” he said, referring to factory farms. “We know these are just petri dishes of disease and contamination.”

A Quiet Collaboration

The new records — two FBI memos and a presentation — reveal a burgeoning relationship between the meat industry and the FBI’s WMD Directive, charged with countering the most serious biological, chemical, radiological, and nuclear threats. Each of the FBI’s 56 field offices has a designated agent (a “weapons of mass destruction coordinator”) tasked with investigating suspected uses of WMD.

Back in Texas in 2019, Holmes Foods, Texas’s largest privately owned chicken producer, tipped the feds off to Meat the Victims’ entry into a factory farm on January 26. The company purchases chickens from the poultry broiler the activists entered.

Just a day after the action, the chicken producer contacted the Dallas FBI outpost for “guidance on preparing for future incidents,” the records show. The following morning, the local WMD coordinator got on the phone with company executives and other local FBI agents to gather information about the incident.

Holmes Foods’ executives told the FBI that “no damage or product loss was immediately identified” in the poultry barn. Yet Dallas’s WMD program documented the incident as part of its intelligence gathering on “animal rights environmental extremism,” which the FBI considers a form of domestic terrorism. This was collected “for situational awareness purposes,” the records show — a phrase that some claim law enforcement agents use as a cover to surveil activists exercising First Amendment rights. “What they call situational awareness is Orwellian speak for watching and intimidation,” Baher Azmy, a legal director at the Center for Constitutional Rights, previously told The Intercept.

Holmes Foods declined to comment.

This collaborative relationship between the FBI’s WMD outpost in Dallas and the meat industry continued into the following year.

The Meat Institute (formerly North American Meat Institute), the largest trade association for poultry and livestock industries in the United States, invited a federal agent to its 2020 Animal Care and Handling Conference to “provide insight into agroterrorism and federal law enforcement’s approach to protecting the United States meat industry,” the records show.

At the virtual conference, the agent for Dallas’s WMD program presented a slideshowtitled “Agroterrorism in the Meat/Livestock Industry,” before a crowd of over 80 attendees largely from the meat industry. The agent detailed the “emerging” WMD and domestic terrorism threats posed by animal rights activist groups — naming Meat the Victims as well as Direct Action Everywhere, or DxE — which often break minor criminal laws, such as prohibitions on trespassing, to bring attention to animal cruelty.

The agent warned that these “minor criminal actions associated with animal rights activist extremism have a tendency to escalate toward substantial direct actions, to include the unintentional introduction of biological materials, toxic chemicals or other hazards into a herd and/or flock,” the records note. The agent also encouraged industry groups to report this type of civil disobedience to its WMD Directive or Joint Terrorism Task Forces, displaying a map of all the FBI’s field offices.

The agent then gave a glimpse into the legal strategy the FBI has been exploring, including potential charges under three federal criminal statutes that cover biological forms of WMD. One statute defines a WMD as “any weapon involving a biological agent, toxin, or vector” and specifies that the damage inflicted by a WMD can conclude the “deterioration of food.” Another statute relies on the same definition for a WMD, but criminalizes sharing information about how to make or use these unconventional weapons.

The agent also noted that the Meat the Victims activists in Texas were “charged with misdemeanor criminal trespass,” but also “emphasized the potential [domestic terrorism] and WMD food sector connections,” suggesting that this is the type of activism the bureau might target with criminal charges.

Will Lowrey, the legal counsel for Animal Partisan, noted the stark contrast between the FBI’s apparent willingness to protect the meat industry and its attitude toward those concerned with protecting animals. “The activists are in a different position when it comes to the government than the meat industry, which can reach out to the most powerful law enforcement agency in the country and say, ‘We want you to talk to us and help us figure out how to defend against these people,’” he said.

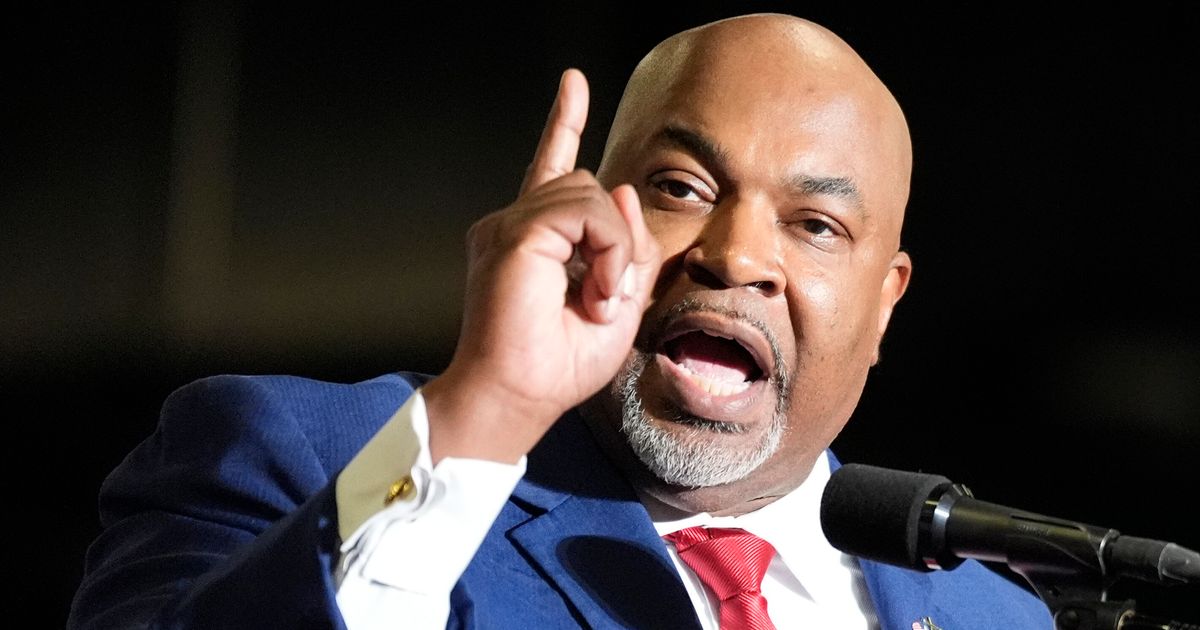

Photo: Direct Action Everywhere

Bioterror Allegations

The FBI has tried to frame animal rights activists as biosecurity and infectious disease threats in at least one other known instance. In 2019, the FBI’s field office in San Francisco claimed that activists with DxE were breaking into poultry facilities and rescuing birds with “little to no regard for basic biosecurity measures” according to a memo first published by reporter Lee Fang. Citing a handful of journal articles, the FBI determined that this contributed to the spread of Newcastle disease, a highly contagious bird illness.

Zoe Rosenberg, an organizer with DxE, said that the group goes “above and beyond” the biosecurity protocols laid out by federal and state agencies. That includes wearing a biosecurity suit, gloves, hair net, and shoe covers while interacting with any farm animals. Upon exiting a facility, “all of that protective equipment is sealed and disposed of safely, just in case it is contaminated with any bacteria or virus from within the facility,” said Rosenberg.

Even still, in Rosenberg’s ongoing prosecution for felony and misdemeanor charges stemming from an action last year, a local California prosecutor painted her as a bioterror threat.

Weldon, of Meat the Victims, said the Texas poultry farm she entered didn’t lock its gate or barn door, so “they’re obviously not too concerned about biohazards,” she said.

The most serious risk, she added, would have likely remained hidden without the activists’ intervention. “Nobody is coming in there and cleaning up the dead bodies,” said Weldon, referring to the chicks. “If there’s disease, you know, disease is just going to spread rampant.”